Cet article est aussi disponible en français.

For several years I have been firmly convinced that the long-term success of OpenStreetMap is intrinsically linked to the resilience of local groups of contributors, their vitality and their independence.

The structure of the numerous local communities is very heterogeneous.

In France, we are an very active community, organised around the OpenStreetMap France association which is officially recognized as a chapter by the foundation.

Collectively, we have already achieved a lot: BANO (Base Adresses Nationale Ouverte (National Open Adresses Database), Umap, Osmose, OSM data, Ça reste ouvert (It stays open), Projet du mois (Project of the month) … We have a tile server with a specific French rendering, a (brand new!) in-house geocoder, we are influential on the country’s open data policy which, despite everything, is improving, in particular thanks to government institutions like data.gouv.fr.

However, this collective organisation is far from being evident in every other countries.

Maps.Me tourist’s invaded countries

The Maps.Me app is widely used by backpackers. The feature of downloading all the data of a country on their smartphone is very popular with travellers. Personally, it allows me to translate the places I go to into French and English.

However, during a trip to Myanmar, I truly realized the extent of Maps.Me’s influence on OSM.

In particular:

- The tourist spots are all very precisely mapped, but some remote villages do not even appear on the map.

- The Burmese alphabet is not frequently used in the

nametag. The de facto accepted local tagging is that of the romanisation ofname, with a compromise using a specificname:mytag to use the local alphabet. This disturbing state of affairs seems to me to be linked in particular to the default configuration in Maps.Me. - Many places exist as duplicate in OSM. In particular, gas stations (for example this one) are regularly duplicated a few meters away. This degradation of the data, which I have observed many times, comes directly from a limitation of Maps.Me whose display of POIs remains random, even at the most precise zoom level leading to contributors inadvertently creating places that already exist. The interface of the app therefore directly influences the poor quality of the data.

- Many place names indicate information only useful to tourists. For example this pagoda is called « beautiful sunset ». In the beautiful Bagan Valley, it is a common practice to include such a practical information for visiting in the name. While it is true that as a tourist, this information has been very useful to me, it is not relevant at all in OSM. The Maps.Me development team should take the situation more seriously and allow tourism meta-data to be added in their own database and not in OSM.

Beyond these aspects related to the contribution tool, the main problem is obviously that there is no organised local community ready to take care of the country’s data.

Looking more closely, we see that the five most active contributors in the country do not reside there. In addition, traditional communication tools (wiki page, mailing-list, etc.) are rarely used.

Striking example: I had to create the sport=chinlon tag and wiki page myself to indicate chinlon fields, despite this being the most popular sport in the country!

Young Burmese practicing Chinlon

To the best of my knowledge, there is currently no contribution or cartographic rendering tool that takes this sport into account

The great wealth of OpenStreetMap lies not in its data but in its community.

This situation deserves more attention. This requires both improving tools and joint efforts to bring about the emergence of a real, active, local community able to enrich OSM itself with its local specificities.

In a country with such a lack in local contributors, remote mapping guided by artificial intelligence is now successful in achieving large-scale success.

Risks and opportunities of AI

Guided in part by their desire to counter the ubiquitous Google Maps, companies like Apple, Microsoft, Facebook and other major digital players have been investing heavily in OpenStreetMap for several years. Their approach, which is very Californian, is first and foremost centered on solving complex technical problems.

For Facebook, the Map with IA project allows the automatic detection of routes through deep learning techniques applied to aerial photographs. After a rather controversial first phase of fully automated integration in Thailand, Facebook realized the importance of human validation and developed the RapiD tool.

This combination of the power of automatic detection supported by human manual control (a posteriori) quickly gives much more accurate results meeting the expectations first set out by Facebook.

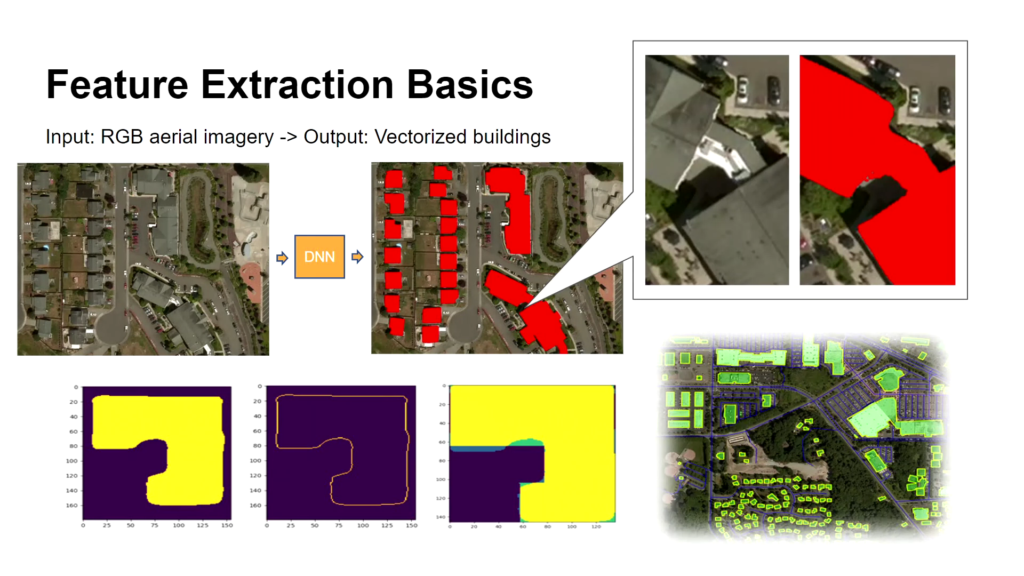

Microsoft also has its machine learning project, properly named « assisted intelligence » in order to detect the outline of buildings and integrate them into OSM. The combined presentation of Microsoft and HOT (Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team) during Sotm 2019 presents this exciting project in detail.

The algorithms detect buildings from aerial views with quite an astonishing precision

Many other similar projects exist and it’s true that greater automation of tasks enabled by technology is already bearing fruit.

The improvement of existing tools also reinforces these results. That is the case, for example, of the use of the Tasking Manager from HOT, for which an upward long-term remote contribution trend is confirmed (see the presentation of the University of Heidelberg at SotM 2020 about it).

However, remote mapping will never completely replace the work on the ground carried out by local communities. Therefore it seems to me that we still have work to do to grow or even create permanent communities in many countries.

The magic formula for a sustaining local community

The ideal method for creating a sustainable local community does not exist, and we must constantly juggle the different local needs.

When carrying out an OSM project outside of OECD countries, the primary needs to be covered are of several types: amenities, hardware, software, training and support.

- The amenities and equipment are necessary for the concrete realization of the project: have a computer, a smartphone, an Internet connection, a room to meet, a bus ticket to go mapping…

The microgrant programme from some chapters (for example in the United Kingdom) but also from HOT (Microgrant and Device grants) are effective in solving these problems. - The case of software is more delicate. To create data in OSM, you are spoiled for choice: JOSM and iD on computer, Maps.Me, Vespucci or Street Complete on mobile, to name only the most famous. However, in many cases, it is still necessary to create the tools yourself, which requires a significant investment.

In my own experience, I participated in the creation of the Jungle Bus app (open source and available for free on the Play Store) which is focussed on bus stops, the website and mobile apps “Ça reste ouvert” to allow the community to spot the places staying open during the Covid-19 lockdowns, or the (brand new) “Projet du mois” (Project of the month) website to mobilise the community around specific topics for a limited time. - Training and support are very dependent on the skills of the locals and should always be thought of à la carte.

With no doubt, human competence is essential. Indeed, beyond achievingshort-term projects, the primary vectors of long-term involvement remains the deep motivations of the contributors.

For each contributor, you have to ask yourself the question « Is OSM a simple side-project or the pillar of his or her career? » The variation in responses seen between these two extremes are numerous and are closely linked to the personal development of each respondent. Asking this question is key to putting in place the best structure for each local community in the long term.

What problem are we trying to solve?

Beyond the questions related to the success of the project (including amenities, hardware, software, training and support), the question that should always be asked is: « What problem are we trying to solve? »

If the answer is « create data to support a specific goal » then you have to dig deeper. Data is never more than a medium for solving more fundamental problems. OpenStreetMap being a data centric project, it is common for this fundamental question to be underestimated in the community.

It is not easy to precisely identify the real world problems to be solved. Here are a few select examples:

Pour l’association Openstreetmap Maroc, disposer d’une carte incluant le Sahara occidental comme partie intégrante du territoire marocain était un prérequis indispensable pour impliquer toute autorité locale. L’affichage de ce territoire contesté n’est pas conforme à la position marocaine sur OpenStreetMap.org. C’est pourquoi l’association OSM Maroc, avec le soutien de l’association OSM France, a mis en œuvre un serveur de tuile destiné au Maroc sur son site web.

For the OpenStreetMap Morocco association, having a map including occidental Sahara as part of the Moroccan territory was an essential prerequisite in order to implicate any local authority. OpenStreetMap.org website display isn’t fitting with this. That is why OSM Morocco, supported by OSM France association, opened a dedicated tile server on its website.

On the contrary for Nathalie Sidibe who launched the OSM community in Mali, « open data makes it possible to fight effectively against terrorism and for humanitarians to step in under better conditions » (source).

With these two examples, we can therefore see that very specific needs depend closely on the local context and can vary greatly from one country to another.

In many regions, the main need is for very different subjects. We can cite risk prevention (floods, earthquakes, … see on this subject the excellent work of the French association HAND (Hackers Against Natural Disasters), the creation of an addresses dataset, an agricultural land register or a public transport map. My company, Jungle Bus, has specialised in this last need.

60% of cities in the world do not have a transport map

This is an issue which Jungle Bus has sought to address in recent years.

In all of our projects, we systematically provide the necessary inputs (amenities, hardware, software, training and support) but also take into account the impact on the development of the local community.

Thus, we always ensure to train members of the local community while strengthening relationships with key local stakeholders.

For example, during the mapping of the transport network of Abidjan in Ivory Coast (see the result in OpenStreetMap), we organised training in the Ministry of Transport’s office in cooperation with the OpenStreetMap Côte d’Ivoire association.

We also made sure that the members of the community had access to an office in the ministry for several months allowing for direct access to the GIS experts.

Joint Jungle Bus – OSM Côte d’Ivoire training at the Côte d’Ivoire Ministry of Transport, 2020

Beyond the magic formula

The problem we are trying to solve, beyond « producing quality data for traveller information », is to involve local contributors in the maintenance of the data, of pushing them to invest in OpenStreetMap in the long term, even after the end of our contract. This is only possible by creating a local open data community related to transport that is not only focussed on OpenStreetMap.

Jungle Bus’s offering therefore goes beyond simply applying a « magic formula » that would meet the needs of the local community (by providing amenities, hardware, software, training and support) and offers specific and engaging solutions to a wide range of local stakeholders.

Towards resilient local communities

For all these reasons, the salvation of OSM in countries where the community is not structured will come from the resilience of local groups of contributors, their vitality and their independence.

This can only happen with the combined action of contributors investing in OSM while looking seriously at solving problems exogenous to the OSM universe (such as transport mapping being addressed by Jungle Bus) and of those who invest in the long-term development of local communities (such as Les Libres Géographes or the Open Cities Africa program).

So I pose the question to you, what do you think is missing for us to succeed in building a truly global and decentralised OSM community?